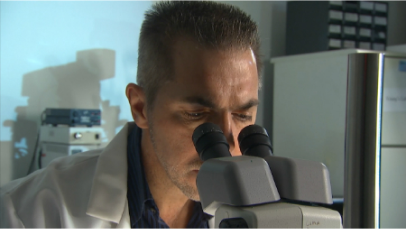

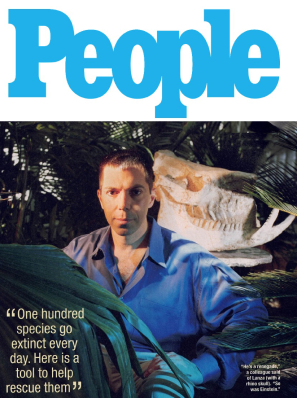

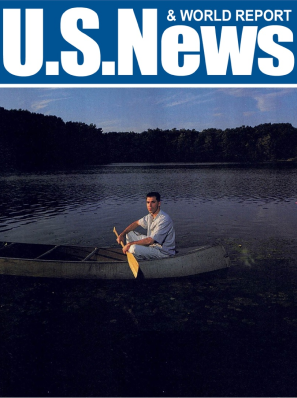

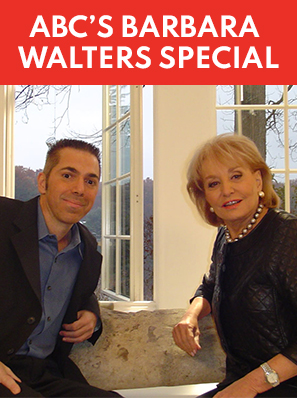

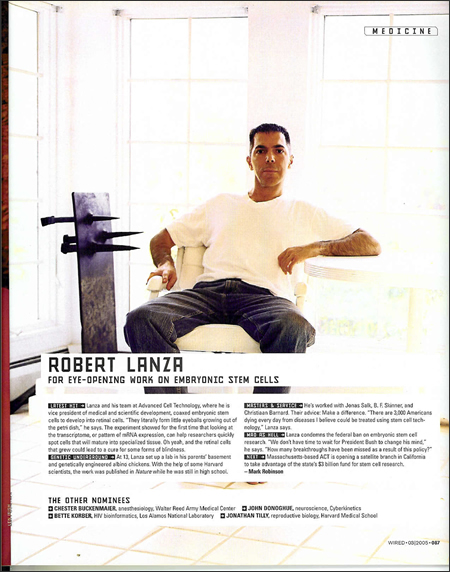

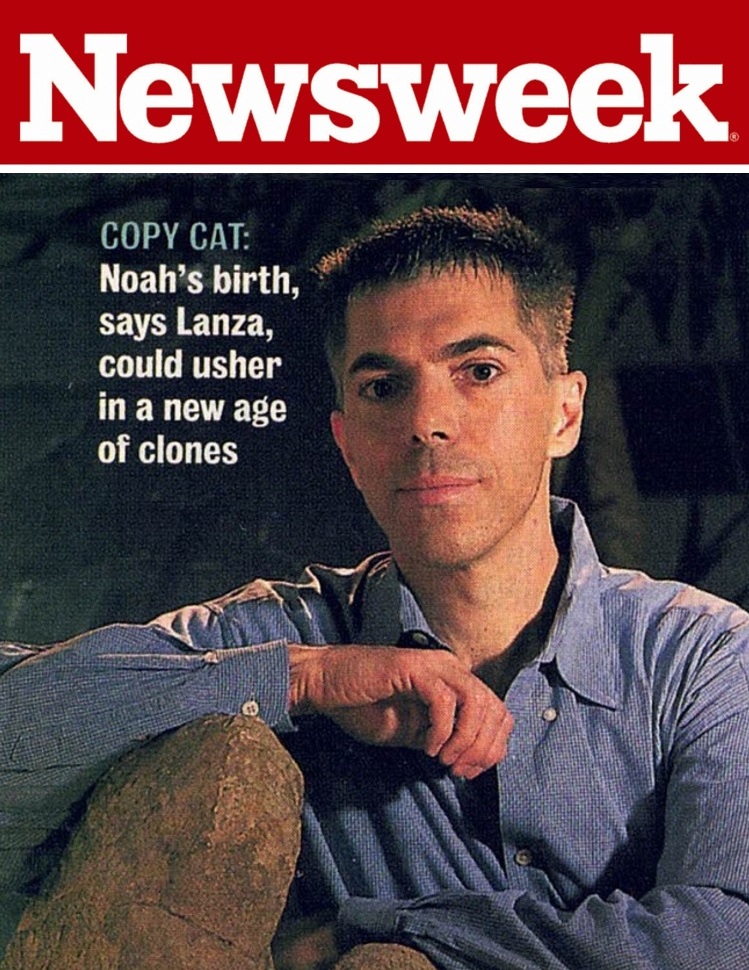

Since he was a child, Dr. Bob Lanza has been fascinated by science and human health. He spent his early years attempting to better understand how the cells in the body interact and how they had a special capacity to restore health. At just 13, he carried out experiments where he restored pigmentation in albino chickens that were subsequently published in the widely-respected science journal Nature. Lanza has since established himself as one of the preeminent researchers in the field of regenerative medicine. Now the head of Astellas’ global regenerative medicine development activities and CSO of Astellas Institute for Regenerative Medicine (AIRM), he has dedicated his life to medical discovery, working alongside Nobel laureates and renowned immunologists and transplantation experts to identify breakthroughs that can change the lives of patients around the world.

We sat down with Lanza to learn more about what inspired him to pursue a career in science, his views on the field of regenerative medicine and the future of AIRM.

How did you get started in this field?

Before starting medical school, I worked with Dr. Jonas Salk, the immunologist who discovered the polio vaccine. He was a wonderful human being and mentor – I saw what he had done for the world and I wanted to be like him. That began my interest in immunology and transplantation, and I went to South Africa to work with Christiaan Barnard, who performed the world’s first heart transplant. We published a dozen papers together, as well as the first book on heart transplantation.

However, after heart transplantation became a conventional therapy, I moved into the area of cell therapy. In early 1999 I joined Ocata, a biotechnology company recently acquired by Astellas. Although the term “regenerative medicine” hadn’t been coined yet, that was the path I was starting down.

Can you explain the concept of regenerative medicine – what is it doing that other therapies are not?

The goal of regenerative medicine is to repair or ‘regenerate’ worn out or diseased parts of the body. This can be done using cell therapy, which generate new, healthy replacement cells to help the body repair itself. Cell therapy is one of the most dynamic therapies ever proposed – they can do amazing things that drugs simply can’t. They’re smart and can hone in to damaged parts of the body.

There are hundreds of diseases caused by tissue loss or dysfunction, and while we’re still at an early stage with regenerative medicine, it’s moving very rapidly.

In addition to ophthalmology, what other diseases can benefit from regenerative medicine?

Regenerative medicine has enormous potential for a wide range of diseases, from diabetes to heart disease. Since starting with Astellas, we have expanded the scope of our research beyond ophthalmology to include the study of cell therapy to treat lung and vascular diseases, in addition to lupus, Crohn’s disease, and other immunological disorders.

We have been investigating whether these cells can be used to treat pain, Alzheimer’s disease in mice, and even fistulizing Crohn’s disease in a dog model. And this is just a small sampling of the type of diseases that could benefit from regenerative medicine.

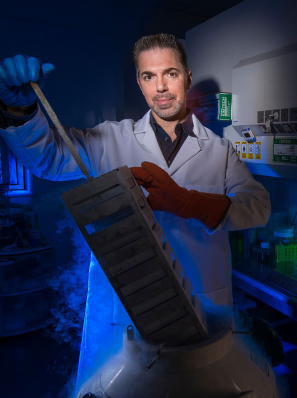

What kind of clinical trials and research is going on within AIRM now?

We recently carried out the first human clinical trials studying the use of retinal cells derived from stem cells as a potential treatment for dry age-related macular degeneration (AMD) and Stargardt disease. These are the leading causes of adult and juvenile blindness, respectively, affecting more than 30 million people worldwide. There is currently no treatment for either disease. In our Phase I/II trials, we injected retinal cells into patients with advanced disease, many of whom were blind.

What aspect of this work are you most excited about – in general and through AIRM?

I’ve seen people very near and close to me die from diseases that I believe we could have prevented with cell therapy. For instance, my father died of COPD (chronic obstructive pulmonary disease). We’re studying cells with one of the top researchers in the world that may one day have the potential to treat this condition.

In the early days, when I first started to work with Retinal pigment epithelium (RPE) cells, a police officer came to my office one morning. He had read an article in the Wall Street Journal about a paper I’d recently published generating RPE cells from human pluripotent stem cells for the first time, and the potential of these cells to treat forms of blindness.

The officer started talking about his teenage son, and how his degenerating eyesight would leave him blind in a few years. I almost had tears in my eyes. We had cells that were frozen down for over a year that we couldn’t even study because we didn’t have the proper resources. I was thinking, “Every year that we stall, all these people are going blind. This is real.”

So it is exciting to know we might have the ability to treat some of these devastating diseases in the future.

What does regenerative medicine mean for the future of therapy and treatment?

I think regenerative medicine has the potential to revolutionize medicine. It could provide therapies for some of the world’s most deadly, debilitating conditions – diseases that currently have few or no available treatment options.

I’m excited to be working at AIRM to change tomorrow.