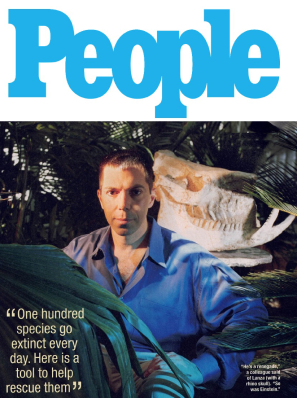

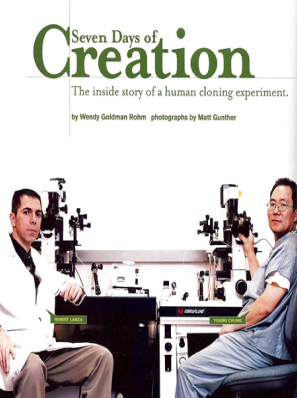

Adapted from The Grand Biocentric Design, by Robert Lanza and Matej Pavsic, published by BenBella Books (2020).

Mounting scientific evidence points to an astounding conclusion about a familiar, everyday (or every night) phenomenon: dreams.

The secrets dreams can unlock ultimately derive from the basic fact that reality is a process that involves us—a conscious observer. We assume the everyday world is “out there” in a more real or independent sense than is the world of our dreams, that we play a lesser role in its appearance. Yet recent studies show that day-to-day reality is every bit as observer dependent as dreams are.

As explained in the new book The Grand Biocentric Design, everything we experience is simply a whirl of information occurring in our heads. Indeed, space and time are not actual physical objects, but rather terms that designate the tools our mind uses to assemble information. They’re among the most critical keys to consciousness, and they explain why, in experiments with particles and the properties of matter itself, they are always relative to the observer, as opposed to being objective, stand-alone absolutes.

Dreams and everyday reality are the same process

As we go about our lives, we take for granted the way our minds put everything together because the process is effortless, and its underlying mechanisms are baked-in, hidden, and automatic. But you might not have suspected that this same process of fashioning a seemingly external 3-D reality is the one underlying dreams. Since the realms of dreams and wakeful perception are usually classified separately—with only one of them regarded as “real”—they’re rarely part of the same discussion. But there are interesting commonalities that give us clues as to how our consciousness operates. Whether awake or dreaming, we are experiencing the same process even if it produces qualitatively different realities. During both dreams and waking hours, our minds collapse probability waves to generate a physical reality that comes complete with a functioning body. The result of this magnificent orchestration is our never-ending ability to experience sensations in a four-dimensional world.

The genesis of the dream realm begins with the simple fact that all organisms sleep. Sleep consists of periods of dreams, called REM sleep, and also of periods without dreams, non-REM. When we awaken we often remember our dreams, but we have no memories of whatever was going on during the non-REM period of sleep. That’s because, during a non-REM period, the wave packet is so widely spread that most of its branches are decoupled from each other, with no interactions or entanglement between them. On awakening, you find yourself in one of those branches, experiencing your familiar world. During dreams, however, the branches of the spreading wave function are not totally independent and decoupled; once back in consensus reality, then, memory has access to those other branches/worlds.

We’ve all had the experience of waking up from a dream that seemed every bit as real as everyday life, even if the sights and experiences were ones entirely unfamiliar to our waking selves. I recall one, looking out over a crowded port with people in the foreground. Further out, there were ships engaged in battle. My mind had somehow created this spatiotemporal experience out of electrochemical information. I could even feel the pebbles under my feet, merging this 3-D world with my ‘inner’ sensations. Life as we know it is defined by this spatial-temporal logic, which traps us in the universe with which we’re familiar. Like my dream, the experimental results of quantum theory confirm that the properties of particles in the ‘real’ world are also observer determined.

We dismiss dreams because they end when we wake up. However, the duration of the experience is poor reason to diminish it. Certainly we don’t think our experience of day-to-day life is less real because it ends when we die. It’s true we don’t remember events in our dreams as well as we do those occurring in waking hours, but the fact that Alzheimer’s patients may have little memory of events doesn’t mean their experience is any less real.

Turning information into a multidimensional tapestry

Dreams are far more than the spontaneous, random firing of neurons that some insist they are. They must likewise be far more than the activation of random memories already contained in the brain’s neurocircuitry. True, dreams often contain a mix of emotions and things we have previously experienced, but in dreams there are often people, faces, and interactions that the dreamer has never experienced before. A dream is an instantaneous, nonstop narrative that often seems as real as real life itself. How could this tapestry of enormously complex interactions and scenarios be the result of nothing but random electrical discharges? In dreams we’re not just watching an “external world” and passively imprinting memories in our neural circuitry. How is it possible for the brain to do this? How are all the components of the experience fabricated from scratch? While dreaming, we’re not observing events and perceiving stimuli. We’re in bed, asleep—yet our minds are able to flawlessly create new people and settings and have them all interact effortlessly in four dimensions. We’re witnessing an awesome occurrence: the ability of the mind to turn pure information into a dynamic multidimensional reality. You’re actually creating space and time, not just operating within it like a character in a video game.

While it’s easier to appreciate the astounding nature of this process when it comes to dreams, it’s the same process that applies to our nondream lives. According to biocentrism, we’re always not just observing but creating reality.

And, as in “real” life, in dreams the collapse of probability waves is a critical component of the multidimensional realities the mind creates. We collapse probability waves in our dreams just as we do when we are awake. During dreams, however, the brain has fewer limitations since it needn’t obey sensory inputs that themselves are limited by physical laws, and thus the mind can generate experiences unlike the consensus world we’re aware of during the day.

Observers define the structure of reality

Now, new research, by theoretical physicist Dmitriy Podolskiy, in collaboration with the author, and Andrei Barvinsky (one of the world’s leading theorists in quantum gravity and quantum cosmology) has revealed something remarkable—that the presence of extended networks of observers defines the structure of physical reality and spacetime itself. In dreams, we leave the consensus universe and can experience an alternate cognitive model of reality—very different from the one shared by other observers while awake. In dreams, the fine structure of the wave function of the universe around us is delocalized and thus largely unstable. This explains why you often have more power while dreaming; the values of observables representing the basis of reality are more fluid. As also explained in the new paper, the presence or absence of observers influences the very dimensionality of the universe.

Biocentrism says space and time are tools of the mind, and dreams seem to be only further proof of the truth of this statement. For if space and time were really external and physical as is popularly believed, then how would it be possible to create something absolutely indistinguishable from them within the confines of one’s dreaming brain?

We think that our experiences at night are only dreams, and that they aren’t real. But dreams and what we perceive as reality are basically of the same nature. By following the implications of quantum mechanics in an unbiased way, we arrive at the unification of everyday reality and dreams. And persistent puzzles regarding the nature of dreams, reality, and our own lives, all fade away.

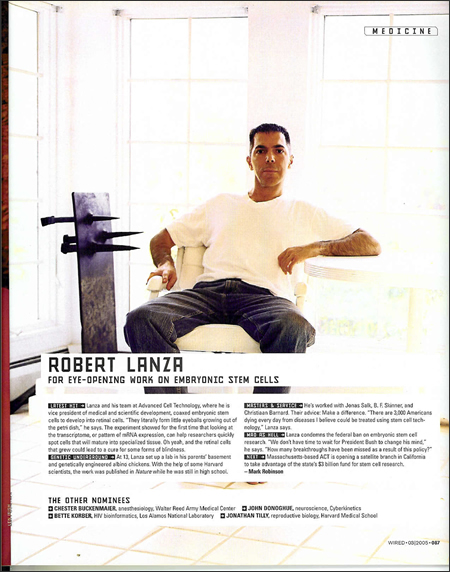

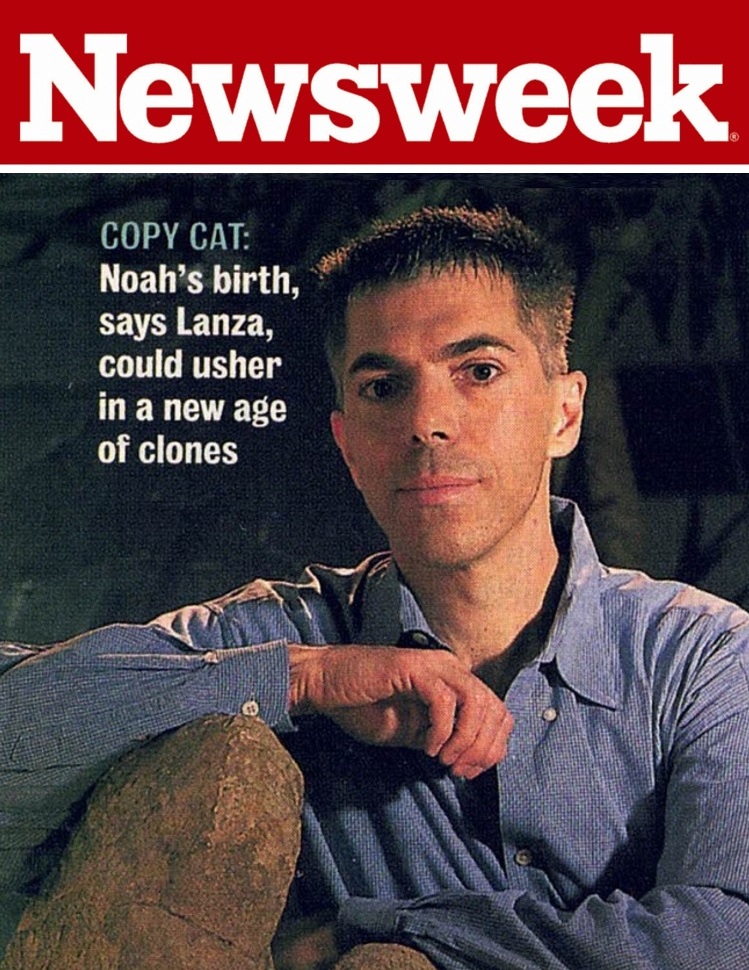

Lanza’s new book “The Grand Biocentric Design” lays out his theory of everything.