“Researchers see the start of a second set of tests, in blindness, as an important landmark for the stem-cell field.”

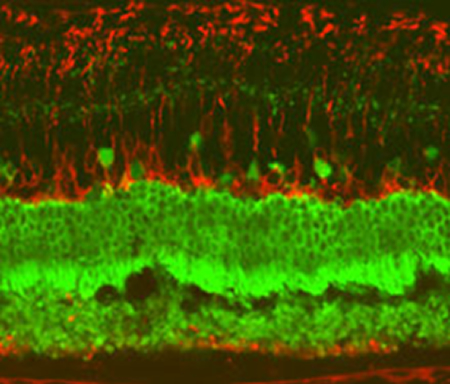

Eye opener: A confocal microscope image of a rat retina after injection of human retinal pigment epithelium cells.

Credit: Advanced Cell Technologies

In a bid to harness the potential of embryonic stem cells, surgeons in California have implanted lab-grown retinal cells into the eyes of two patients going blind from macular degeneration.

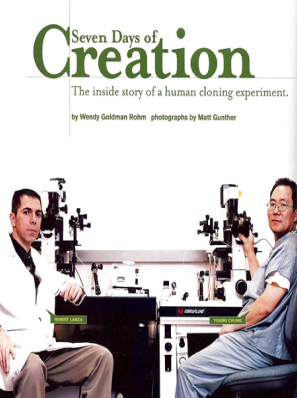

The procedures were carried out on Tuesday by Steven Schwartz, chief of the retina division at the Jules Stein Eye Institute at the University of California, Los Angeles. They were financed by Advanced Cell Technology, a biotech company with laboratories in Marlborough, Massachusetts, that recently won approval from the U.S. Food and Drug Administration to test the treatment in 24 patients suffering from either dry advanced macular degeneration, or a juvenile form of the disease known as Stargardt’s.

The two patients, whose names weren’t released, are among the first volunteers ever to receive a treatment created using embryonic stem cells. Last year, another biotech company, Geron, began a small study using stem cells in a bid to repair spinal cord injury.

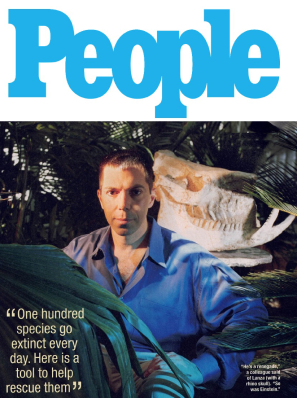

Researchers see the start of a second set of tests, in blindness, as an important landmark for the stem-cell field. It is also a major step for Advanced Cell, a tiny firm that has long been at the center of stem-cell controversies. Anti-abortion protesters once protested outside the company, and investors were fearful. Twice the company laid off nearly its entire staff when its bank accounts hit zero.

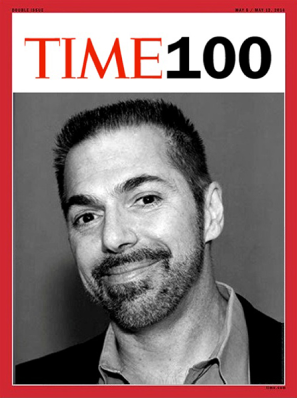

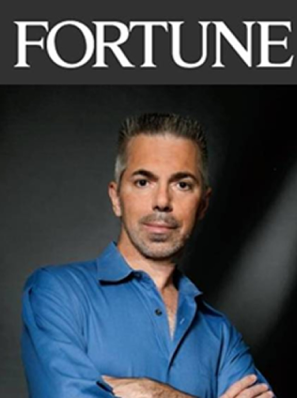

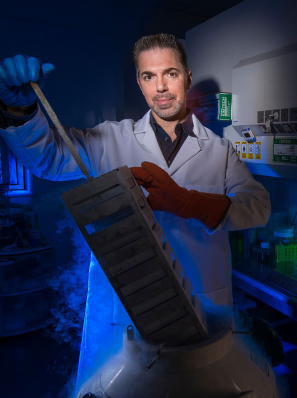

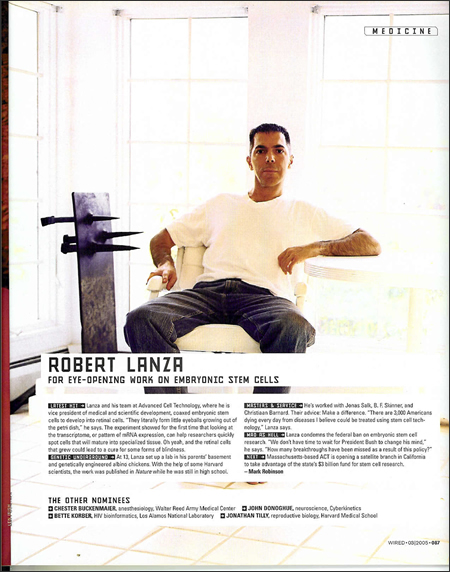

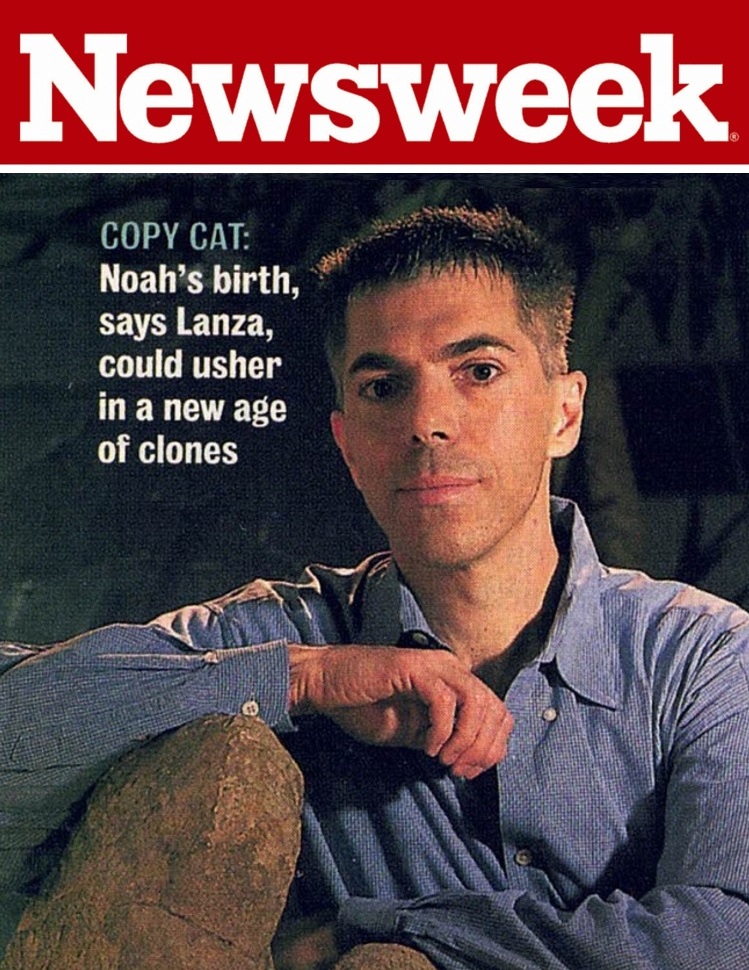

“Things were crazy for a long while,” says Robert Lanza, medical director at Advanced Cell, and one of 22 full-time employees. “Times have really changed. The field is much tamer now.”

The start of the clinical trials is likely to stir hopes of a big payday among investors. Advanced Cell’s stock price has risen 170 percent during the last year, valuing the firm at $285 million based on Tuesday’s stock price. Investors hope it could be worth several billion should the therapy succeed. Nearly 10 million Americans suffer from some form of macular degeneration.

So far, however, embryonic stem-cell research has been a money loser. Advanced Cell has run up losses of more than $180 million since it was founded in the mid-1990s. In recent years, it sold off programs for cloning cattle, and abandoned controversial efforts to clone human embryos in favor of a narrower approach.

“We are excited about this treatment, because we think this has the potential to slow the disease progression,” said Steve Rose, chief research officer of the Foundation Fighting Blindness, a nonprofit that invested about $2 million in early animal testing of the treatment, but is no longer directly involved. “This company has had their ups and downs, and I am really happy to see they got into the clinic. We’ve had our fingers crossed.”

During a recent visit to Advanced Cell’s laboratories, a research technician adjusted a microscope to show off the company’s lead product: cube-shaped retinal pigment epithelial cells growing in a petri dish. Some were translucent, while others already had the brownish coloring of a mature cell. (The pigment absorbs stray light in the eye, acting as a kind of glare shield.)

These retinal cells are the type that are killed off in macular degeneration, eventually leading to the death of photoreceptors, and the gradual loss of central vision. Advanced Cell believes that injecting new, lab-grown cells into the eye may cure the condition.

Embryonic stem cells can grow into any other type of human tissue. That’s why they have been touted as a potential cure for everything from Alzheimer’s disease to alopecia. But the reality is that applications are likely to be far more limited, at least in the near term, Lanza believes.

It’s no accident, for instance, that both early studies of embryonic stem-cell therapies—those of Geron and Advanced Cell—involved cells of the nervous system. The reason is that embryonic stem cells naturally want to make neuroectoderm, a cell lineage in the embryo that forms the nervous system.

“Embryonic stem cells have a mind of their own, and they want to do certain things,” says Lanza. Efforts to produce other cell types, such as liver cells, have proved far more difficult, he says.

Another obstacle not always fully considered is immune rejection. Many have suggested that embryonic stem cells could cure type 1 diabetes if researchers could transplant lab-grown islet cells. But such a treatment could require powerful immune suppressing drugs whose side effects, such as infection and cancer, can be as bad as the disease they are meant to treat, or worse.

Lanza says that is why all the early embryonic stem-cell trials are targeting body areas such as the spine, brain, and parts of the eye, where the body’s defenses against invaders are blocked, at least partially, in a phenomenon known as immune privilege. “Nature has got to cooperate,” says Lanza. “That is why a lot of companies went out of business, and we didn’t.”

View article at technologyreview.com