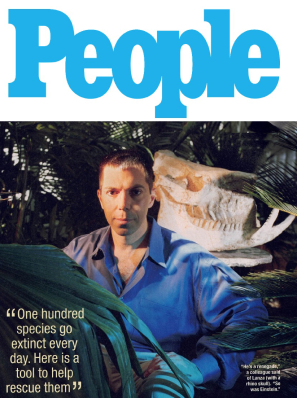

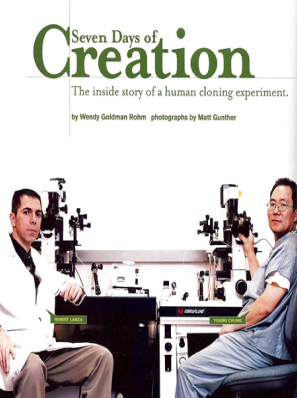

Adapted from The Grand Biocentric Design, by Robert Lanza and Matej Pavsic, published by BenBella Books (2020).

“We patronize [the animals] for their incompleteness, for their tragic fate of having taken form so far below ourselves. And therein we err, and greatly err.” —Henry Beston

It’s natural to be people-centric when exploring consciousness. We’re all drawn toward the familiar. But we’re just beginning to understand our own human consciousness, making it surely even harder to probe that of, say, an octopus. But subjective experience and the exquisite and varied processes that facilitate perception are indeed also enjoyed by creatures very different from us. They may possess neural architecture quite distinct from the structures of the human brain, architecture that is nonetheless clearly designed to enable consciousness to be centered or localized within it. The neural structures of an organism’s consciousness are evolved to impart singular experiences tailored for specific situations and habitats.

As to how conscious experience manifests in nonhuman life forms, one broad difference might be familiar thanks to a recent development in primary education—an emphasis on “mindfulness,” a practice dating back to ancient meditative traditions that (based on data showing its effectiveness at improving concentration) some teachers have now been trained to suggest to students. Those just now hearing the term may take it to suggest time spent in thought, but the practice of mindfulness actually involves the opposite. The idea is to be attentive to immediate sensory experiences rather than ruminating about this or that. If students can simply observe whatever they see or hear, paying attention to the unending details unfolding in the present moment rather than daydreaming, they will be sharper, keener, and derive more benefit from the here and now, including the classroom experience. Bottom line: the huge brains we’ve been given can be as much a distraction as a gift. This kind of being “in the moment” is the type of consciousness that, as far as we know, most corresponds to that of other conscious organisms.

By “other conscious organisms” we mean animals—including birds and insects—that have brains, sense organs, and appendages that allow them to locomote and move around in space, as well as animals and plants that do not actively move, but that can store memories and respond to their spatial environment. Mindfulness might bring us more into sync with the experiences enjoyed by nonhuman animals, but the differences in our conscious experiences obviously run far deeper than the unique human penchant for daydreaming. Some organisms utilize sensory inputs that are entirely absent from our own awareness, or if present, have through time slowly degraded until they now play negligible roles in daily life. Once we begin to take a look at animal consciousness, we find ourselves in an almost endless exploration of strange new worlds. Remember—as explained in my new book The Grand Biocentric Design—reality exists relative to a particular observer: animal consciousness, like human consciousness, involves the collapse of wave function. And the unique physiological setups of other animals allow their choices and wave function collapses to unfold along pathways that diverge from ours in wonderfully creative and useful ways.

For example, everyone who has ever had a dog knows where most of a canine’s attention is centered. On smells, of course. Just check out that nose! It starts just below the eyes like ours does, but then extends halfway to Florida. Is it any surprise that 90 percent of Rover’s attention is on environmental chemistry?

But our dog’s consciousness diverges from ours in ways more dramatic than time spent on smells. Dogs have recently been shown to sense magnetic fields!

We’ve long known that bees, birds, termites, ants, hens, mollusks, many bacteria, homing pigeons, chinook salmon, European eels, salamanders, toads, turtles have magnetotactic abilities, in some cases caused by their central nervous systems responding to chains of magnetosomes, which are tiny specks of iron-rich minerals like magnetite surrounded by membranes of fatty acids and, typically, more than twenty proteins. This architecture is so wondrous, and produces a sensitivity so acute, that some animals create a mental plot of subtle variations in our planet’s magnetic field, providing an internal road map of their location.

The fact that dogs might also exhibit this kind of magnetic talent was suspected long before it was proven because of their curious preference for relieving themselves with their bodies aligned north-south. No matter what biome or environment a creature inhabits, nature’s innovativeness in meeting its challenges and conferring advantages seems virtually limitless. Take, for example, the detection of infrared, or heat.

Bats, of course, are most famous for a different sensory ability, one that’s even more alien to us. This is their sonar mechanism, in which they chirp a continuous series of sounds and then detect sonic reflections that reveal the distance to some flying prey or a cave wall they wish to avoid. They can even get information about a target’s movement by discerning the echo’s Doppler shifts, similar to the pitch changes we perceive when a car horn or ambulance siren is moving toward or away from us. These sophisticated talents are impressive enough, but echolocation abilities reach astonishing perfection in toothed whales and dolphins, whose sound pulses can penetrate soft tissue to provide them with an X-ray-like mental image of the object of interest.

Dolphins have still more up their little sleeves. They have the ability to reproduce the echoes of their own sonar signals, so that when they have found something interesting, like a delicious school of juicy fish, they can replicate the sounds to “tell” other dolphins what they’ve discovered. In doing this, they don’t employ the kind of clumsy, symbolic, one-word-at-a-time process we humans use for communication. Instead, they actually create a visual picture of what they just saw in the minds of other dolphins, perhaps even “bolding” or “highlighting” aspects they wish to emphasize.

So far, we’ve mostly explored the ways animal consciousness can operate by detecting what to us are invisible emanations. But what about mechanisms for detecting more straightforward, tangible stimuli—like actual substances hitting us? One such mechanism gives rise to what we experience as sound.

To settle that old barroom argument over which organism has the best hearing (What? Maybe you don’t go to the right bars…), the answer is the moth. Moths can detect even higher-pitched sounds than bats can—which is saying something, since the latter is the creature they’re most desperately trying to evade. The bat comes in at number two, and after that the keenest hearing belongs to the owl, then the elephant and the dog, followed by cats. The worst hearing? Probably snakes, whose consciousness is naturally and understandably more attuned to ground vibrations than fluctuations in air pressure.

Through it all, it’s good to remember that though the animal body is the instrument of sense perception—like a big neuron antenna—all sensory data is ultimately processed in the brain. The brain receives nothing but impulses, a ditdit ditditditdit ditditdit of electrical signals carried from the senses to the nerves. The brain receives broken-down information and has to put this disjointed mass of data back together, which it does according to very specific laws. It reassembles sensory data according to the rules of time and space—the logic of the brain.

As explained in The Grand Biocentric Design, time and space are projections created inside the mind, where perception, feeling, and experience begin. They are the tools of life, the representations of intellect and sense.

Sight, smell, hearing, touch, and taste are our familiar human sense “instruments.” Various animal species share various of these five senses in various wattage intensities, and as we’ve seen, may also employ other senses we might find hard to intuit.

In biological terms, the logic expressed in the circuitry of the brain is linked to the logic of the peripheral nervous system. They are coordinated. The differences in wattage and instrumentation among animal species circumscribe the universe distinctly for each.

Animals and humans are able to discern multiple sense perceptions as existing alongside one another at the same time, observing them as objects existing outside us and as occurring in space. A human being, for example, might perceive the scent of lilacs bursting from bright spring clusters poking through a chain-link fence from a fertile backyard into an alley where trash cans overflowing with ripe garbage reek in the pale light of an overcast sky while a plane roars overhead. And yet for all these conscious sense-mediated experiences—a potpourri of unending sensations—we humans sometimes place ourselves in a radio-static mode, attuned to no sense whatsoever, lost in the internal world of our thoughts until we suddenly realize a friend has been speaking . . . and wonder if that “mindfulness” business might not be such a bad idea.

Lanza’s new book “The Grand Biocentric Design” lays out his theory of everything.